In this coastal town, rising seas exacerbate high-tide flooding

Anatomy of a flood

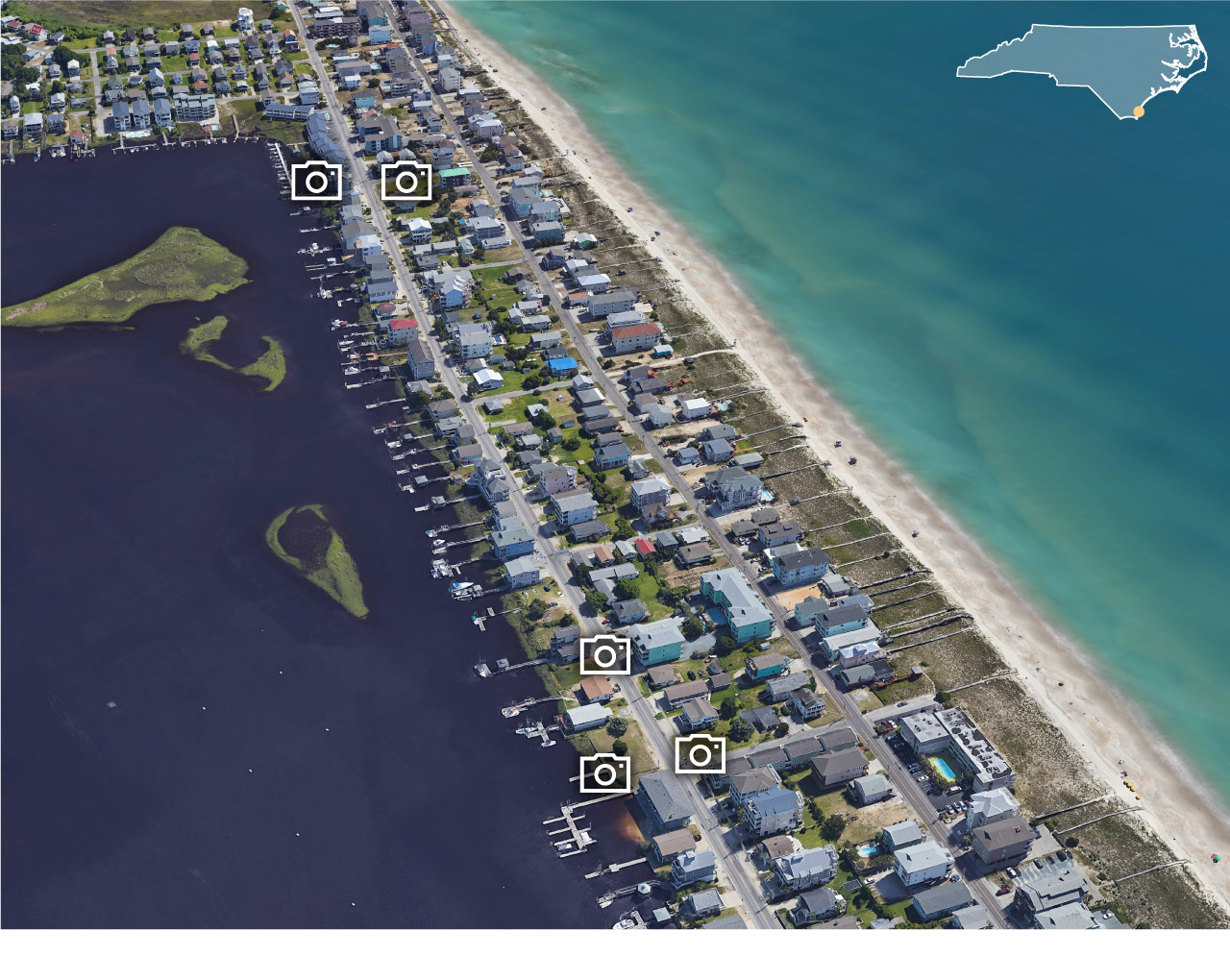

The Post installed cameras along the main road of one N.C. town to document the many ways rising seas exacerbate high-tide flooding.

CAROLINA BEACH, N.C.

Nothing seemed amiss on a warm late-summer afternoon in this laid-back beach town south of Wilmington.

Surfers tested the waves rolling in from the Atlantic. Kayakers drifted across the sparkling bay just to the west. Bicyclists pedaled past colorful wood-frame houses with names such as Ship Faced and Sand Dollar Retreat.

But even on this postcard-perfect day, a threat was lurking — one that is growing more disruptive, more often, in coastal communities in the southeastern United States:

Sea-level rise.

In a matter of hours, a particularly high tide would once again arrive in this town of nearly 7,000, overwhelming its outdated and overmatched infrastructure. The main drag of Canal Drive would once again become submerged by floodwaters.

The Washington Post had set up cameras in multiple places along the road, capturing in real time the many ways that ever-higher tides exacerbate flooding, and why local efforts to cope with this growing scourge are often falling short in communities where seas are rising the fastest.

The videos illustrate how, even on days without major storms, rising waters are compromising stormwater infrastructure, overtopping shorelines, elevating groundwater, and combining with rain to make flooding more persistent and more insidious over time.

The images add to growing evidence captured by scientists who, day after day, are documenting the frequency of these sunny-day floods in an area where sea levels have risen 7 inches since 2010 — among the highest in the country, according to a Post analysis.

In several coastal North Carolina communities, researchers have installed sensors inside stormwater drains and cameras along the streets above to record the causes and number of floods.

In Carolina Beach alone, they have documented 60 days over the past year when Canal Drive flooded, many of those during clear weather. That’s far more than the four to eight high-tide floods projected by the federal government for the same period, based on measurements from a nearby tide gauge.

The Drowning South

Tide gauges designed to record changes in sea levels “are only painting part of the picture” of what is happening on land, said Katherine Anarde, an assistant professor of coastal engineering at North Carolina State University who is helping to lead the research.

She and her colleagues, working to decipher a fuller picture in specific places, keep arriving at the same conclusion.

“It is flooding more than we know,” she said.

Two days in Carolina Beach— the first clear and calm, the second marked by rain — show why fixing the deepening problems of sea rise poses such a daunting task.

Day 1

A sunny late-August day in Carolina Beach. In the early afternoon, around low tide, Post journalists set up time-lapse cameras in several spots along Canal Drive to capture what happens as the evening high tide arrives.

2:45 p.m. — 7:15 p.m.

As the tide rolls in, a stormwater pipe at Seahorse Lane steadily becomes submerged by salt water.

The stormwater pipes and drains along this stretch of Carolina Beach were built generations ago, when they were above the high-tide line. But as this part of the southeast Atlantic coast experiences one of the most rapid sea-level surges on Earth, high tides regularly swallow the infrastructure that is supposed to drain city streets, leaving water nowhere to go.

“The higher tides are lingering more often. When we do have an event, it’s multiple days,” said Jeremy Hardison, planning and development director for Carolina Beach. “There’s definitely more water in the pipes and drains than there used to be.”

City officials have worked to combat the worsening problems, but it’s an uphill battle. They have installed backflow preventers to try to keep seawater from filling outflow pipes, though such retrofitting can have uneven results. The harsh coastal environment speeds wear and tear. Barnacles grow on the edges of valves, compromising their watertight seal.

“Water doesn’t need much to penetrate in,” Hardison said. “In some areas, it has helped; in some areas, it hasn’t performed as we thought it should.”

Local leaders also have mulled raising roads and building more bulkheads, he said. But such approaches can prove expensive, face regulatory hurdles and public skepticism, and come with the risk of unintended consequences.

On this day, seawater eventually fills a pipe near Seahorse Lane, causing water to spew from a drain 45 feet away onto Canal Drive.

6:40 p.m. — 7:30 p.m.

As rising seawater fills a stormwater drain, the excess quickly floods onto Canal Drive.

Besides overwhelming drainpipes, rising sea levels also push up underground water levels — commonly known as the water table.

“As the sea level gets higher and higher,” Anarde said, “the groundwater table also increases.”

That means there’s only so much capacity for the ground to absorb any rain that might fall. “So even just a minor rainfall event can lead to ponding in low-lying areas and just can exacerbate the flooding in the roadway or in yards,” she said.

As high tide approaches on this clear day, puddles of water appear from seemingly nowhere in certain spots along the street and at the base of a nearby power pole and stop sign.

6:36 p.m.

As rising seas force groundwater to the surface, water starts to bubble up from cracks in the pavement.

The most obvious manifestation of rising seas is the higher tides that more easily send water creeping over shorelines.

That is what happens at this empty lot along Canal Drive — one of several places unprotected by a bulkhead.

5:15 p.m. — 7:50 p.m.

The incoming tide submerges a low-lying lot before spilling onto the main road. It pushes through marsh and across the once-dry land, turning it into a temporary pond. As sunset approaches, it continues to spill over onto the nearby street, covering it completely and making it impassable for many vehicles.

In a handful of hours, this combination of factors transforms a long stretch of Canal Drive into a canal. And most of that flooding arrives swiftly, overtaking the road in barely half an hour around high tide. As dusk arrives, the water is more than a foot deep in places, despite the clear, calm weather.

The city often must close the street to traffic on days with tides like this, said Hardison, the city planner. “It’s a given,” he said.

Police officers arrive to lower a series of gates the city installed several years ago that warn of the latest saltwater intrusion. “Road closed,” the signs read. “Saltwater flooding.”

A few drivers in trucks plow through anyway, sending ripples of water to lap off nearby carports and garage doors.

As sea levels continue to rise, Anarde says, these types of floods will happen during more high tides, linger longer and cause only more damage. “It’s just going to get worse,” she said.

8:06 p.m.

By nightfall, the unstoppable tide stretches along Canal Drive and up side streets. Floodwaters creep up driveways and meander under some raised houses. Televisions flicker inside nearby homes, and the light from streetlamps dances across the water that has swallowed the road outside.

Day 2

The remnants of Hurricane Idalia are barreling past the Carolinas. On this day, more than 3 inches of rain fall on Carolina Beach — not insignificant but also not an unheard-of amount for a storm along the coast. The day offers a firsthand lesson in how sea-level rise is making “compound” flooding more severe.

11:50 a.m.

A steady rain settles in over Carolina Beach. “When it’s high tide and it rains, there’s nowhere for that water to go,” said Hardison, the city planner. “If there’s nowhere for that water to go, then it’s going to back up and fill up like a bathtub.”

3:30 p.m. — 6 p.m.

Stormwater pipes again fill up with seawater as high tide arrives, leaving no room for rainwater to drain.

Surging sea levels combined with even modest rains lead to what scientists call compound flooding, and it is happening more often in more places.

Pipes that once would have drained by gravity are now filled with salt water, leaving no escape for precipitation.

6:50 p.m. — 7:30 p.m.

“The system gets overwhelmed,” Anarde said of the rain that falls hard along Canal Drive. “As sea levels continue to rise and we see tides propagating higher and higher, plus the frequency of these rainfall events, we’re going to see more-frequent flooding for a lot of communities — even at moderate or lower tides.”

As darkness arrives, Canal Drive is once again submerged, this time even deeper than the day before. Authorities once again lower the gates to block the street. It will be hours before the floodwaters subside.

Over the past year, researchers have logged dozens more flooding events along Canal Drive than official estimates from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, whose scientists say high-tide floods in the South are already happening five times as often as just several decades ago.

Federal tide gauges “are not actually intended to measure flooding on land,” said Miyuki Hino, a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill environmental social scientist.

It is a gap scientists are busy trying to better understand as this type of flooding worsens. “Measuring the floods correctly is a prerequisite for measuring the human impacts correctly,” said Hino, Anarde’s research partner.

As time goes on, and the trend continues — seas are predicted to rise as much as an additional foot along this stretch of coast by 2050 — these floods will force hard questions in coastal towns.

“Absent significant investments in adaptation, we’ll see a rapid increase in the incidence of chronic flooding relative to what we are seeing right now,” Hino said.

And definitely not just in Carolina Beach.

“A lot of coastal towns across North Carolina and across the U.S. are facing this problem,” Anarde said. “The last 10 years are not a good indicator of what the next 10 years will look like.”

About this story

John Muyskens contributed to this report.

Editing by Monica Ulmanu, John Farrell and Joe Moore.

Project editing by KC Schaper. Copy editing by Carey L. Biron and Martha Murdock.

Additional support from Jordan Melendrez, Shibani Shah, Erica Snow, Kathleen Floyd and Victoria Rossi.

How we reported the story

Over two days late last August, The Post set up cameras in various locations along Canal Drive in Carolina Beach to capture flooding during multiple high tides. Each camera took a photo every 10 seconds. The photos were combined in postproduction to create the time-lapse videos in this story.

The Post’s visit coincided with a “king tide” — a term commonly used to describe some of the highest predicted annual tides at a particular location. These events occur several times a year in many coastal areas, and offer an opportunity to see what average water levels might look like in the future as sea levels continue to rise.

Water levels measured in the Carolina Beach Yacht Basin

The approach to capturing the multiple drivers of flooding was informed by conversations with Katherine Anarde and Thomas Thelen at North Carolina State University, Miyuki Hino at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Adam Gold of the Environmental Defense Fund. A paper they and other colleagues published in 2023 detailed how they used storm drain sensors and roadway cameras to determine that flooding in Beaufort, N.C., was happening more often than nearby tide gauge levels would have predicted.

Researchers continue to monitor the impacts and causes of such flooding in multiple communities in North Carolina, including in Carolina Beach, New Bern and Carteret County — part of an effort known as the Sunny Day Flooding Project.